Exercise and the Heart

Exercise and the Heart

I teach my patients that four essential “ingredients” form the foundation for long-term health: Exercise, Good Nutrition, Sleep, and Stress Reduction. Of these four components, exercise seems to have the most profound impact on longevity and is the focus of this review. Exercise alone, however, does not diminish the importance of the other three factors. Remember that you cannot out-exercise or “sleep off” a bad diet. The admixture of all four pillars is critical for a healthy and happy long life. However, exercise exerts (!) a significant impact on the abundance of health we all seek, and it needs better clarification.

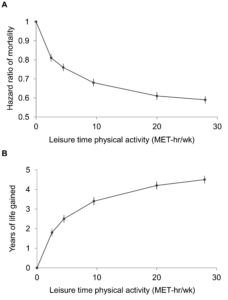

Several studies report a 50% reduction in cardiovascular and all-cause mortality associated with regular vigorous exercise. This data is crucial when you compare the much more meager 3% absolute reduction in cardiovascular mortality provided by statin therapy in the primary prevention of heart attacks. In addition, moderate exercise for 150 minutes/week or longer protects against metabolic disorders associated with enhanced mortality. Exercise alters the magnitude and severity of diabetes, hypertension, lipid disorders, dementia, and osteoporosis. A regular habit of moderate exercise can lead to 5-6 years of additional life and up to 9-10 years of optimum health. This benefit should motivate everyone to maintain or begin a regular exercise habit.

Even small incremental exercise sessions can provide benefits. Although some debate exists regarding the upper limits of exercise duration related to mortality reduction, longer exercise times (up to a point) appear to be associated with more significant mortality reduction. (See image). Some researchers have suggested a J-typed curve when assessing exercise duration and mortality, implying that long duration may adversely affect longevity. There appears to be reasonable evidence that supports this observation. Therefore, more prolonged bouts of exercise and frequent (> three times per week) intense exercise sessions likely don’t benefit the quality and quantity of life compared to less rigorous and shorter sessions. This message should be good news for all but the most fervent exercise enthusiasts.

Image credit: PLOS Medicine 2012

Image Credit: Wikipedia

As you can see from the chart, the magnitude of various exercises is associated with measurements called METs. It is essential to understand precisely what this means to apply logic and understanding to exercise and its role in your health.

A MET measures the amount of oxygen our cells consume during daily life. It is also a valuable tool for identifying the number of calories burned during everyday activities. A MET is the amount of oxygen utilized in milliliters/minute. One MET is equivalent to 3.5 milliliters of oxygen per kilogram of weight per minute (3.5ml/kg/minute). At rest, we typically utilized one MET per hour. It can also be expressed in calories burned per minute when knowing that one Liter of oxygen consumes five calories of energy. For a typical 70-kilogram man, you can identify the number of calories burned over a day by the following method: .0035L of oxygen x 72 kg x 60 minutes = 15.1 Liters of oxygen used per hour. This value can then be multiplied by five calories used/Liter of oxygen to reveal an hourly calorie utilization of 76 calories. Over 24 hours, we can see that a 72-kilogram man will burn approximately 1800 calories at rest. Weight gain is inevitable if he remains sedentary and consumes more calories each day. This scenario is something that I repeatedly see in my clinic. As we age, our daily calorie utilization at rest, known as our basal metabolic rate (BMR), slowly diminishes.

Consequently, we burn fewer and fewer calories at rest. If we eat the same number of calories, we inevitably gain weight! It can be very frustrating and discouraging.

The antidote is exercise. The good news is that exercise has survival and health span benefits even without weight loss. An overweight person who exercises moderately for at least 150 minutes per week can expect a much better survival than their thin and sedentary counterpart. Do not get discouraged if you exercise vigorously and still struggle to lose weight. You are still accruing the survival benefits.

Do not be discouraged by the amount of exercise required. I recommend aerobic training and weightlifting for all my adult patients. Walking briskly three days a week (15 METs total) and lifting weights twice weekly for 1 hour (10 METs) could lower your mortality by up to 40%. It may also provide you with over four years of additional life. These numbers are not inconsequential and should motivate you to get up and go!

How do these numbers translate into life expectancy? In a large study from Harvard-affiliated institutes, exercising for 150 to 300 minutes per week was associated with a gain in life expectancy of 3.4 to 4.5 years. In patients with average body weight, the life expectancy for this level of exercise was more than seven years! The investment opportunity of regular aerobic exercise offers an incredible return on investment and should be approached by everyone who wants to enjoy a fruitful and healthy life.

Resistance exercise (weightlifting) has been independently associated with a mortality reduction of 20%. Weightlifting and other weekly resistance training provide remarkable benefits as we all age. A decrease in fall risk, a reduction in bone loss (osteoporosis), and a decrease in cognitive decline are linked to resistance training. When combined with dynamic exercise (aerobic), the mortality decline is further enhanced to 40%. These numbers cannot be achieved with any medication or other medical treatment. I always recommend an admixture of both types of exercise because it attains the most significant survival and health span outcomes at little to no cost for the patient.

The hazards of exercise appear to be few. Nonetheless, it is always my advice to discuss the institution of the activity or any increase in intensity/duration of your exercise program with your medical advisors. There are a few medical reasons to avoid intense training, including any form of symptomatic heart disease such as chest pain, palpitations, or syncope (passing out). It is also important to undergo screening for such things as Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (unusual thickening of the heart muscle), diseases of the aorta, unique heart rhythms, or any valvular disease of the heart. Most of this screening can be completed with a good physical examination, an ECG, and (if indicated) an echocardiogram. All family history of heart disease or sudden death should be taken seriously and reported to your medical team. Suppose you have multiple risk factors for coronary artery disease (CAD). Considering a Coronary Calcium Score (CCS) to assess your risk may be reasonable, but this can be a double-edged sword. High scores may discourage people from exercising due to fear of provoking a heart attack, even though regular low-level exercise is prescribed after heart attacks, stents, and coronary bypass surgery. High CCS scores indicate a potential higher risk of a future cardiac event, and I usually recommend a stress test before providing an exercise prescription. Interestingly, an elevated CCS is also reported in those on long-term statin therapy and in ultra-endurance athletes such as those participating in frequent marathon and ironman triathlon events. The exact cause for these findings is not unclear, but I believe that Vitamin K2 impairment and repeated exposure to high oxidation levels are possible factors.

There has been some interesting recent research regarding high-intensity interval training (HIIT) and the effect of this training on heart disease and cognitive decline. Studies have revealed that HIIT performed one to two days a week can benefit coronary artery plaque buildup after stenting. There also appears to be some clinical improvement in memory beyond standard exercise in some individuals who engage in this exercise a few days a week. HIIT workouts are generally shorter and more intense, but the benefits can be significant. I strongly advise caution for any sedentary or periodic exerciser if they want to pursue this option. Discuss this plan with your healthcare provider before embarking on this exercise journey.

One final bit of advice is necessary. Exercise does not make you immune to heart disease or other ailments. We know that some people pursue extreme levels of training under the false premise that it assures longevity. This supposition is an illusion. An overabundance of many worldly things is not always good for you. Increases in chronic injuries, diminished immunity, atrial fibrillation, and obsession with exercise are not good outcomes for those on the extreme exercise bandwagon. There is mounting evidence that this approach is counterproductive and potentially harmful to longevity. I believe training for a rare marathon or an Ironman challenge is reasonable. Goal orientation has always been a focus of my life, and I encourage this quality in others. It is the long-term extreme exercise that seems to get us into trouble. In my estimation, this exercise mindset is harmful and should be discouraged. I have never been a good golfer, but this is probably related to the fact that I rarely played. I also felt that golf did not provide me with an adequate aerobic base for daily workouts. When added to my other weekly dynamic and resistance training, I can now enjoy golf’s social and health benefits with friends and family without significantly dropping off my weekly Mets. Incorporating new activities such as pickleball and golf can provide enjoyment, skill development, competitive drive, and socialization, all essential for a happy, healthy, and long life.

To summarize my assessment of this information, let me conclude with the following points:

- Moderate exercise for 2.5 hours per week substantially benefits overall health and longevity.

- More prolonged exercise (up to a point) may further enhance health and longevity and improve metabolic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, and lipid disorders.

- “Long and Hard” as one ages does not appear to be a good prescription for longevity.

- There appear to be clear disadvantages to extreme exercise duration, including a greater risk of musculoskeletal injuries, lowered survival, and the development of cardiac damage, including heart arrhythmias (atrial fibrillation).

- The addition of weekly resistance training can lead to substantial benefits in mortality reduction and lowers overall frailty and fall risk.

- A basic understanding of METts is worthwhile as you incorporate a weekly exercise plan and any weight loss strategy into your lifestyle.

As we pursue a healthy and happy long life, we often meet with resistance. Many of these life events are self-imposed because of poor motivation or laziness. One of the common excuses that I hear is related to musculoskeletal issues such as painful backs, knees, hips, or shoulders. I promise you that none of these complaints will eliminate your capacity to exercise. You must be creative and persistent if you desire long-term health. Your family needs you and wants you around for a long time. Please do it for them!

Dr. Ken Cooper started the world-renowned Cooper Institute in 1970 and is a lifelong proponent of health and prevention. At 91, he still promotes the value of exercise and its role in longevity. He also reminds us that it is much less costly to prevent a disease than to cure or treat it. He also has valuable words for those who would make excuses when we think of exercise.

“We do not stop exercising because we grow old. We grow old because we stop exercising.”

Ken Cooper MD

Don’t be a procrastinator. Enjoy the abundance of health that a regular, active lifestyle promises. Let your lifelong love affair with exercise begin!

Peter Diamond MD